Luxury from the 1999 self-titled sessions

Luxury from the 1999 self-titled sessions

One of the coolest things about doing this zine is not just getting to talk to my favorite artists, but also communicating with other people about great music that means something to us. I really enjoy reading feedback from our readers because it gives us some type of gauge as to how we are doing and how people are enjoying (or not) the bands that we cover and the stuff we have to say. People don’t always take time out of their schedule to drop an email, but sometimes we get some pretty crazy letters, and sometimes we get really cool encouraging emails. Jamey Bozeman sent us a really nice email a few months back. I immediately recognized the last name and Matt and I were pretty sure that it was Jamey Bozeman from the band Luxury that was one of the original Tooth ’N Nail artists. Fortunately it was.

It was really cool to catch up with Jamey and talk about Luxury and what he is up to now. We were trying to get his brother Lee in here also, but they both have pretty constant demands on their time and we just couldn’t get Lee in here. I highly recommend that you purchase this music if you haven’t already. Like so many other great artists, Luxury was ahead of the time for the Christian industry. They came out on a label that was breaking into the scene in a big way, and they were a unique act for the Tooth ‘N Nail roster who mostly signed much heavier acts at that time. It was a moment in time in the music world, one that was welcomed, and one that is missed.

Can you give me a history of Luxury and who the players were?

The beginnings of Luxury were with our drummer, Glenn Black, and with me at Toccoa Falls College, where we played in a band called “Various Artists” between 1988 and 1990. Chris Foley and my brother Lee enrolled at TFC in 1990, at which point the three of us (Lee, Chris and me), plus drummer Todd Monroe, started a new band that was eventually known as “Flagday.” Todd moved on in 1991, and Glenn, Lee, Chris and I formed a new band combining these two previous groups. What we started would become “The Shroud” in 1991, and included guitarist David Jarvis. Eventually David stepped down, and I stepped back in after taking a short break from the band.

By January of 1992, between fall and spring semesters at TFC, Glenn, Chris and I began writing songs that were more aggressive and less Cure-ish, if you will. Up until this point, we had drifted into very moody, atmospheric writing, and our new musical ideas were taking us away from those roots. Lee was away over the winter break, and returned to find something new happening with us musically. That was a turning point for us musically and as a band. After experimenting with the line-up and the sound for quite a while, we were starting to solidify what we were after musically. That is to say, we were still pretty unfocused stylistically (were we going to sound like The Smiths or Fugazi?), but we were now focused enough to begin becoming a “real” band.

The Shroud made some initial 4-track recordings with David Jarvis in 1992, and then later (as we were improving our writing and performance skills) recorded a four-song demo with Andy Lemaster (now better known for producing a number of cool bands and for his own band Now It’s Overhead and his work with Bright Eyes). This four-song e.p. was called Tinsel. This was our first legitimate demo, and it helped to break us into the Atlanta music scene. In early 1993, we recorded a full-length release called Candy Darling, again with Andy Lemaster. The whole thing was recorded on a Tascam 8-track cassette multi-track recorder. It was utterly low-tech by today’s standards, but I still have a soft spot in my heart for that amazing piece of technology. We recorded in Toccoa, our home base of sorts, and at the all-ages club that we ran at the time, called “The Dish.” We really wanted to promote music in our tiny southern town, and The Dish was our way of doing just that. We brought in both local and touring bands, some of whom later became known on a national scale. As a side benefit, we were able to essentially stay at home and reap the benefits of getting to know a lot of other bands without needing to do a lot of traveling.

Like so many other bands, The Shroud began to experience its own inner turmoil. The four of us were starting to differ in our personal and musical visions and we made the decision to split up. We were scheduled to play at I.S. Fest in Atlanta in the summer of ’93, and we determined to make that show our farewell to our small group of fans. What actually happened prior to playing this festival was that by taking a break from the band we found that we really missed it and each other’s company. We played that last show and realized that the four of us had something special. Perhaps not earth-shattering, but certainly significant. Before the festival had concluded, we had determined to get back together, recanting of our decision to end the band.

It wasn’t too long before we decided to give the band a complete make-over. We were going to make a break with our past and forge a new future. I can’t remember exactly when it happened, but at some point Lee suggested that we re-name the band “Luxury”. I’m pretty sure that this suggestion was not met with unanimous enthusiasm, but the idea and the name stuck.

By the summer of 1994 we had recorded another demo, called (rather simplistically) “the pink tape,” as it was a cassette with a nifty pink cover. Several of these songs would appear on our first official full-length album. We made the fateful decision to drive to Cornerstone Festival that summer, and make the attempt to play the impromptu stage where we might showcase ourselves for Tooth and Nail. We really had no interest in any other label at the time because we were so impressed by the bands on the T&N roster.

We drove to Cornerstone in a borrowed Ford station wagon. After arriving, Glenn promptly had an epileptic seizure; only the second that he had ever had. Obviously, this was neither a good omen or a great way for Glenn to spend his first day at C-stone. We spent the remainder of the festival meeting people and trying to promote Luxury person to person, as much as possible. We managed to meet Jeff Cloud, who was (and is) very cool, as well as some members of Blenderhead, as I recall. After multiple unsuccessful attempts to be selected to play the impromptu stage, we were finally picked. It was the last day of the festival, and we had actually planned on leaving that morning. We opted to stay and try one last time, and found ourselves on stage in the blazing sun at 1:30 in the afternoon. I don’t believe that we played all that well, but I think Lee really put on a good show. The Blenderhead guys really liked it, and Brandon Ebel seemed quite impressed. He took us aside and offered us a deal right after we were done playing. It was quite a memorable moment for all of us, I think. I drove back to Georgia that night, taking Glenn with me, along with Zach and Russel from Joe Christmas.

We began recording Amazing and Thank You in October of 1994, at Neverland Studios. Steve Hindalong produced and Chris Colbert engineered. This was an incredible experience for me. Steve had been a long-time musical hero of mine, and working with him and Chris was simply fantastic.

In support of the new album, we spent part of Spring 1995 touring with The Prayer Chain. Again, this was an incredibly formative experience for us, getting to know these guys who would continue for years after to be influential as friends and fellow musicians.

Everything changed for us after our first trip to Cornerstone as a Tooth and Nail band, in the summer of ’95. We were gathering momentum at that point, playing a lot of shows and planning to expand into regular touring. We were becoming a professional band. We played to a packed tent at Cornerstone, and felt that we had really arrived. On our way back to Georgia, however, our driver lost control of the van that several of us were in, and rolled it across the median of I-57 in Illinois. What followed was months of recovery for my brother Lee and Glenn, along with a lot of soul searching. Both Lee and Glenn suffered severe injuries in the accident, and the band was sidelined until we could decide how to continue, if we were going to continue at all.

By the spring of ’96, after we all had a chance to recuperate and consider life as a touring band, we began writing again. The result of this was The Latest and the Greatest, which was recorded outside of Athens, Georgia in the summer of 1996. Not too long after this, we went on what would be our second and final tour as Luxury, teaming up with Morella’s Forest. By the end of 1997, we were starting to drift in different directions once again. We still played occasional shows. For the most part, we lived near each other and were able to continue working together on a basic level, but it was becoming obvious that we weren’t going to pursue the band and a mutual career in music the way that we had originally conceived.

In 1998, however, we got the itch to record a few songs. We had previously parted ways with Tooth & Nail, partly due to our vision for a band/label relationship (which Tooth and Nail did not necessarily share) and partly due to our own inexperience and naiveté. Long time friends David Vanderpoel and Marty Bush had started a label called “Bulletproof” to which they were beginning to sign bands. We began talking to them about our interest in releasing another record, and they brought us on board. We recorded what we call the “self-titled” album with Matt Goldman at our studio in Toccoa and at his in Atlanta, starting in late 1998 and stretching into 1999. Matt did a fantastic job capturing our sound, helping us to do justice to the new songs that were literally coming to life as we recorded them. As a side note, we ended up buying back about 1,000 copies of this album when the distributor went bankrupt. I still have those CD’s stored away, and we still sell a few now and then.

By 2001, Luxury had become a side-project to our lives. Up until this point, all of us except Glenn had remained in tiny Toccoa, Georgia. Glenn had relocated a few years previous to Asheville, North Carolina, which wasn’t too far from Toccoa. But by 2001, Lee was preparing to move to the Kansas City area, and Chris had begun to consider his options. I had been playing in another band, Canary, that had more-or-less evolved out of my continuing desire to make something out of my musical ambitions. Canary later became They Sang As They Slew, and we signed with Northern Records. Even so, Luxury remained alive in a very small way.

In 2003, Lee suggested that we try to put out an EP, and offered three song ideas to work on. What actually happened was that Northern offered to release a full-length record instead, if we could assemble the songs. Lee went to work writing, and I began the process of recording what was to become Health & Sport, which was released by Northern in 2005. In the process, we brought on Matt Hinton (of Piltdown Man) to play guitar and fill out the sound. These recording sessions were the last time that Luxury assembled in its entirety.

All of us have remained active in music on some level, whether by releasing music by way of other bands or simply by continuing to play generally. Glenn, who continues to suffer from epilepsy, has tried to keep active playing drums with friends locally, as well as by introducing his oldest son Nicholas to the world of rock music. Chris is now Father Christopher, an ordained priest in the Orthodox Church in America. He still occasionally is able to pick up a bass guitar and make music, though his calling as a pastor and a father and husband leaves little time for such activities. Lee and I have both continued to write music and release it. Lee works under both “All Things Bright And Beautiful” and “Orient Is His Name”, releasing music both through Northern and the bandcamp.com site. I worked with They Sang As They Slew (a.k.a. Canary, a.k.a. The Canary Islands, and so on) for over ten years, releasing albums under our own imprint (The Cut & Paste Collective) and on Northern Records, as well as on bandcamp.com. Lee and I are also attending St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary, where we are each pursuing ordination and our master’s degrees.

All of which brings us up to 2011.

When did you guys sign with TnN records, and how young of a label were they at that time?

We signed with T&N in 1994 at Cornerstone Festival. They were fairly new at the time. I believe that Amazing and Thank You was something like release number twelve. So we were a part of that initial phase of the label, I suppose.

What were some of the primary obstacles that you had to overcome as a band back in the 90’s?

In some ways, to be a band in the 90’s was tougher than it was prior to and after that time. We were on the cusp of the revolution that the internet was about to bring, and we couldn’t see it happening at the time. When we started, bands like us were primarily concerned with recording at a dinky, 8-track studio and putting out cassettes or 7-inch vinyl. We would use our land-line phones to call around for gigs (cell phones were essentially unheard of), and we would play to audiences that had no way of knowing who we were prior to us coming to their venue. There was no MySpace or Facebook or such. There were ‘zines and proper magazines, and if you were good enough or edgy enough (or both), then you had a shot at getting some exposure that way, but that was about it. This seems like such a constraint by today’s standards, but in so many ways it was easier and simpler. These days, nearly anyone can release anything at the click of a mouse or the push of a button. We are utterly inundated by useless, average, unnecessary music, and the good music often is lost in the shuffle, literally.

To find cool music at that point of time (the 90’s, before the internet took over) was like finding a treasure. It was a challenge, and you valued your music collection accordingly. These days, music has become disposable due to the ease and abundance of recordings available. Music has truly become a product in so many ways. Gone are the days of sifting through the cutout bin at Camelot, and I (for one) miss those days.

In the 90’s, bands faced less of a challenge to be heard. It was still by no means easy to get the attention of a record label, but the musical landscape was a far cry from where things are today. The rule of the day in the 90’s was “adaptation”. Suddenly, we were starting to book shows via email, which was entirely novel at the time. The music industry was in transition from analog to digital, from cassettes and vinyl to CD, and eventually to MP3. Music videos, which had previously been the domain of major label acts, were now becoming common for even small bands. Because of all of this, the demands on bands became much greater. We had chosen to “make our stand” in a small town in Georgia, making it that much more difficult for us to meet these demands.

Regardless, we were able to release multiple albums essentially on our own terms. We were never terribly successful according to the standards of the music industry, but we made decent art and tried to manifest the creativity that had been given to us by God.

After leaving TnN records you guys signed with Bulletproof, correct? Why did you leave TnN for another label?

We didn’t get along all that well with Tooth & Nail. Some of that might be legitimately blamed on the fact that we had spent so long working from the D.I.Y. perspective. We liked T&N initially because in so many ways it fit our preconceptions of a musical community. The bands on the label at that time tended to see themselves as “Tooth & Nail bands”. We certainly understood ourselves in this way. We had always liked labels that presented themselves in this manner, such as Dischord, Adult Swim, Teenbeat, Merge, and so forth. I suppose these days that sort of thing is simply called “branding”. We had strong “punk rock ethic” tendencies, and lacked the experience needed to deal with a label that was heavy on the business side, as T&N was. There is nothing wrong with being heavy on business, it just didn’t suit us as it turned out. We were far too casual in our approach, though I would hardly call Luxury a group of slackers. We simply had our own time frame, our own ideas concerning bands and labels, and these didn’t mix well with T&N.

I think that Bulletproof, specifically David Vanderpoel and Marty Bush, had known us for so long and had worked with us that we didn’t have these sorts of problems. We were all from Georgia, and I think we had a more similar mindset, by comparison with our relationship with T&N. We were a different band and different people by the time we signed with Bulletproof, as well.

We used to give T&N a lot of grief over what we saw as their failure to be what we thought that they should be. As time has passed, I think that T&N were simply acting like a business and we didn’t care for their methods. I think that the fruit of their vision has been to become more marginalized and to sign ever more bland bands that sell lots of records. Not that all the acts are bland. Just most of them.

Luxury live at The Mainstream

Luxury live at The Mainstream

Back in the early days of TnN, there were so many great bands, but it also seems that the label oversaturated the industry to some degree with so many acts and not all were of the highest caliber. Did you feel that Luxury got lost in the shuffle to some degree?

It was really up to Luxury to stand out, and due to some circumstances beyond our control and some that we had control over and chose poorly, we failed to gain the audience that we had at one time hoped to gain. T&N had a lot of faith in us initially, but we simply weren’t on the same page. They saw our potential, perhaps more than we saw it, but we were unable to capitalize on their faith in us quickly enough to make anything of it. T&N signed a lot of acts at that time (at least this was so from our perspective) and I think that we did eventually get lost in the shuffle. But, hey, that’s business.

Working as friends can be difficult to some degree, how was it being in a band and working together as brothers?

If there is anything that I miss about Luxury, it is the wonderful comradery that we shared. There were so many good times that we spent together, most of which I utterly took for granted at the time. There is nothing like working to make art with your friends. When the creative muse hits, and you all find yourself in sync, all the gears mesh and the stars align, and then you all sort of look around at each other and try to suppress the grin that’s spreading on your face because what you just played was absolutely amazing… there is nothing like it. You all struggle to give birth to this idea… you fight and argue and things begin to turn ugly… and then you try to make the song happen one more time. And then it happens. I miss this, both with TSATS and with Luxury.

As far as working with Lee is concerned, it could be difficult because he is demanding, sort of specific, and yet sort of vague, presenting a moving target musically that we needed to hit in order to meet his demands. But when everything clicked and we found that he was digging what we were doing, we were rewarded by his enthusiasm, which was a very good thing. For Lee, “close” was never good enough. He’s difficult to please, but if you were able to create something that worked for him, then you probably had created something pretty good.

Having said that, consider the fact that he’s my brother. My younger brother. I’m a bit of a hot-head, and so Lee probably suffered more from our working relationship than I did. I miss being able to work with Lee like we used to in the early days of Luxury.

Do you consider music to be just music, or do you consider it to be art and therefore consider yourselves to be artists?

I think that we as musicians make music, and that we make art. There is high art and low art and everything in between. I think that we were trying to make something that was truly art, knowing that it would simply be the sort of art that’s simply in between. These days, so many musicians simply want to make a buck. Can you blame them? I’d like to make a buck. I think that I may have made more money from my music since I stopped trying to make a career of it than I did when I was really trying. Strange. Luxury was really about making art in one sense, and about simply writing a good rock song in another sense. We were artists in the sense that one cannot help but be an artist if he makes something artistic. Were we true artists or good artists? I have no idea. We literally gave blood, sweat and tears for our art. Maybe that makes us true artists. I really can’t say.

Do you guys feel that music can bridge a gap spiritually, or do you feel that it is purely a form of entertainment?

Well, I am Orthodox Christian, and for us such discussions are more about “both/and” and not so much “either/or”. There is nothing that humans do that is exclusively physical or exclusively spiritual. We are physical and spiritual beings in totality and simultaneously. I can’t compartmentalize what I did as a rock musician on stage from who I am the rest of the week. Likewise, I can’t compartmentalize what I do at church from what I do on stage or elsewhere. Our music is doing something, whether we want it to or not, both to us and to those who listen. We are responsible for every word that proceeds from our lips, and (I would add) every note that screams from our amps. That being the case, in order for us to be living authentically and consistently our music would have to somehow reveal the truth of Christ within us. If I am singing lyrics that are totally out of sync with what I believe, then perhaps there is something worth re-thinking there. At one time TSATS was considering covering Depeche Mode’s “Blasphemous Rumors”, simply because it was such a powerful song. But how could I justify singing those words? How could I actually say such angry things about God that I didn’t feel or believe? That was a line that I drew for myself. It would have rocked, but it would have failed to live up to my own personal rule of authenticity.

What is the responsibility (if there is one) of an artist when it comes to Christians playing music? What I mean is do you feel there is a responsibility with message, content, etc. as it relates to faith?

Our relationship to Christ, which should be a transformational relationship (one in which we are transformed by Christ), should inform our art. I would stop short of suggesting any sort of standard for lyrics or content or style or whatever. My priest has a saying that he uses: “Bless that which is blessable.” To be blessable, something must be able to be offered to God in order that it might be made truly good. If what you do is blessable, then it should be done in a way that it is consistent with our transformation in Christ. I think of the scripture in James that questions whether both salt water and fresh water can come from the same source (James 3:11). Usually, this is used to correct someone’s tendency to use foul language. I think that for Christian musicians, our responsibility is to be authentic. We need not write hymns and we need not feel guilty about writing loud or obnoxious songs. But we should see that everything that we do must be informed by the transformation that has occurred in us. If we have “put off the old man” then why would play music that merely reflects that same “old man” that we have supposedly shed?

Having said that, I would be quick to say that most so-called Christian music simply turns me off. So much of it tries too hard to be “spiritual” and fails to be anything more than sappy words. Others become cynical and drift away from their roots as Christians, perhaps for legitimate reasons, and their music portrays a loss of faith that does little to help anyone and perhaps harms some.

My concept of authentic, honest “Christian” song writing (please understand that I use that term hesitantly) would loosely follow the pattern of the Psalms. The Psalm writers many times would question what was happening around them. They would lament the ills of the world and the falseness of men (even supposedly Godly men). They would even cry out to God, asking “why?”. But they, as a whole, turn their focus back towards God, recognizing that in a broken universe, He is the one consistent, unchanging fact of our existence, and that, ultimately, He is good, indeed the only true “good” that we can know.

Like the Psalm writers, we can lament and expose the falseness of the world around us. We can sing about the darkness and we can weep and cause others to weep. But at the end of it all, if we are not sharing the light and hope of Christ within the context of our art, then we are failing as Christian artists.

- They Sang as They Slew blog

- They Sang as They Slew on BandCamp

- Lee Bozeman’s website

- All Things Bright and Beautiful on BandCamp

- Orient is His Name website

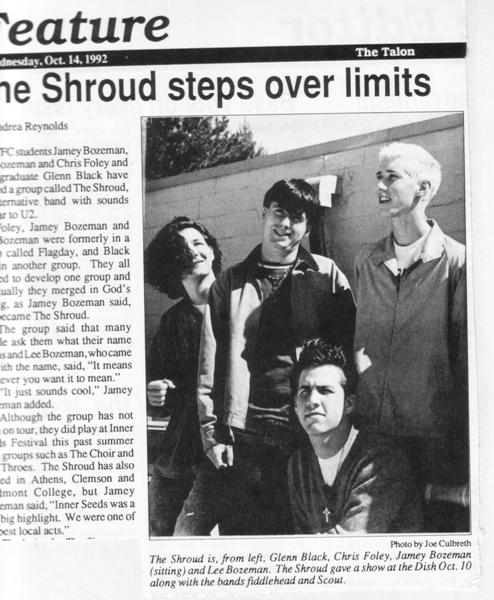

Local article on The Shroud from 1992

Original Luxury Tooth & Nail promo

Jamey Bozeman live in 1999

Luxury in 2004

Leave a Reply